Alles ist Gut

massa critica | michele d’ariano simionato + marco jacomella

Learning from cities has become commonplace in architectural culture since the 1970s, and although Northern Switzerland can seem less inspiring than the Mojave Desert, the social, cultural and economic dynamics that have characterised Zurich during the last fifty years are worth to be acknowledged, so to better understand, among other things, the paradoxical role that counterculture movements can play in the frame of urban transformation processes.

Intro

The early twenty-first century shows a renewed interest in the Western city. After the middle-class migration to the suburbs of the post-war period, contemporary cities are increasing their population and being exposed to real estate speculation, which in many cases brings about social inequality, disposition, and displacement (Harvey, 2008). As public spaces are turning into instruments of economic speculation (Sevilla-Buitrago, 2013), contemporary cities are turning from being a right for many into an asset for the few.

As Lefebvre states in his seminal work The Urban Revolution (1970), cities are constantly produced by a continuous dialectic between opposites, e.g., social rights and institutional order: they thrive, prosper, and evolve thanks to these contrasts. According to the French sociologist, the production of urban space could be then described as the result of a “continuous tension between isotopy – the accomplished and rationalised spatial order of capitalism and the state – and heterotopia” (Harvey, 2012). According to David Harvey, Lefebvre’s concept of heterotopia “delineates liminal social spaces of possibilities where ‘something different’ is not only possible, but foundational for the defining of revolutionary trajectories” (Harvey, 2012).

In a more and more unequal and fragmented society, it is crucial to understand the role of the city, of its citizens and, moreover, of these heterotopias, these Freiräume, namely these flexible, undefined, and out-of-the-market spaces, as a way to challenge inequalities and develop a critical, long lasting, and productive antagonism.

This refers to and questions directly the Right to the City (Lefebvre, 1968), i.e. the “right to change ourselves by changing the city (…), the exercise of a collective power to reshape the processes of urbanisation” (Harvey, 2008), because of the marginalisation and exclusion of many. The reduction of spaces, alternative to the ones produced by the capital, narrows down “the possibilities to reclaim the city for thinking and producing alternatives from both the market and the state control” (Klein, 2001).

Karthago (’81-84), then and now

Karthago (’81-84), then and now

Zurich as case study

Zurich is an illustrative example of some of the concerns and processes expressed above.

A global financial hub, the city has grown and attracted a constant flow of people and capital, thanks to the extremely enjoyable environment it offers. Several reports (Mercer, 2015 and The Economist, 2015), basing their findings on factors as safety, healthcare and environment, helped brand Zurich as one of the most liveable city in Europe.

This success comes at a high cost: the chronicle lack of affordable spaces in the inner city (in 2016, only the 0,22% of the housing stock was free, according to the Department Statistik Stadt Zürich) has been lately worsened by an unprecedented wave of high-end new constructions and urban regenerations (e.g., Europaallee, Zürich-West, Altstetten), triggering visible processes of gentrification and displacement of low income groups, extensive privatisation, and control of the urban fabric.

However, a more accurate look reveals how the success of the city was not only founded on economic grounds, but also built an opposition to them, through many experimental spaces, cultural centres, and social alternatives (Schmid, 1998).

The rise of Zurich to the status of global city has been defined by two very different forces (Schmid, 1998). On the one hand, the fiscal politics, the centralisation of capital and the development of a headquarter economy in the ’70s positioned the city on a global level. On the other hand, a constant presence of grassroots movements opposing the most liberal aspects of this process triggered its social and cultural transformation. This dialectic – with its problematics and contradictions – has thus highly contributed to the definition of the current attractive and lively urban environment of Zurich.

Nevertheless, the early period of intense generation of proposals has been nowadays replaced by a progressive institutionalisation and incorporation of these movements into a market logic. The current situation has lost this fertile juxtaposition, increasing the risk of an impoverishment of the cultural landscape of the city.

Wohlgroth (’89-’94), then and now

Wohlgroth (’89-’94), then and now

A brief historical excursus

In the ‘60s Zurich became one of the main financial centres of the world. The city promoted big infrastructural renovations to adjust to its new role. These projects faced the opposition of big parts of the population, afraid that the proposed changes would transform the friendly small-town atmosphere of Zurich into a cold technocratic vision. Numerous referendums rejected all the major projects proposed by the Municipality, such as the Parkhaus Hechtplatz (1970), Expressstrasse-Ypsilon (1971-75) and the U-Bahn Projekt (1973). This opposition movement merged with the unrests started in Paris in the May 1968 and then spread at European level, creating a climate of tensions between institutions and population. Quoting M. Castells, the “people mobilised to change the city in order to change society”.

The city was shaken by unprecedented agitations claiming social renewal, freedom of expression and measures against real estate speculations – among many others the Globus Krawalle (1968), the Autonome Republik Bunker (1970), Venedigstrasse (1971), Hegibachplatz (1974), the occupation of the Langstrasseunterführung (1978) and the Hohlstrassefest (1979). These protests managed to gather a transversal section of the society, expressing their needs and demands[1].

The refusal of any dialogue adopted by the institutions created a social standoff, which culminated the 30th of May 1980. The accumulated tensions, worsened by the persistent speculative bubble and the rigid positions of the Municipality, exploded in the Operakrawalle, marking the beginning of an “Urban Revolt” (Schmid, 2001) that ceased only two years later, when on the 23rd of March 1982 the AJZ, the social center symbol of the movement, was demolished.

In the aftermath of this turbulent period, the City adopted a new policy towards counterculture. The right-wing administration, faced by the failure of its repressive politics, opted for a softer approach, granting funds, providing infrastructures, and guaranteeing substantial tolerance. The budget for counterculture was progressively risen, increasing from 1 Million CHF in 1982 up to 11 Million CHF in 1990. Numerous experimental social centers were opened by the Municipality, like the Kanzlei (1984), the essay cinema Xenix and the Gessnerallee theater (1989). Finally, in 1989 the policy against occupations was changed: through the adoption of the so-called Genfer Modell, squatters were allowed to remain in an occupied building until its demolition or renovation, if the hygienic and safety standards were met.

This measure was also a pragmatic way to reverse the state of abandonment or underuse of large portions of urban territory at the time. While the urban politics of the ‘60s and ‘70s encouraged a policentric development of the economic and productive centres, the crisis of the industrial economy in the ‘80s relocated parts of the working class from the urban centre to suburbia (Schmid, 1998), causing a further shrinking of the population in the central neighbourhoods. Downtown became thus a slum for the so-called A-Gruppe: Arme, Alte, Ausländer, Arbeitslose, Abhängige (poor, old, foreigners, unemployed, dependent). The situation was worsened by the problem of the open-air drug scene. Started in the ‘70s around the Riviera and Bellevue, the drug market was periodically pushed around the city by the police until 1986, when it was gradually concentrated in the Platzspitz park, transforming it into the traumatic symbol of the degrade of downtown Zurich.

The direct intervention of the institutions avoided the risk of an exploitation of this situation by the private market. The promulgation in 1983 of the Lex Koller restricted the possibility for foreign capitals to buy Swiss real estates, thus hindering possible international speculations. In 1988, Ursula Koch – city councillor and Head of the Public Buildings Department since 1986 – declared in front of the general assembly of the SIA (Swiss Architects Association): “Die Stadt ist gebaut” – the city is already built. The policy of urban redevelopment she started rendered compulsory the use of design plans for the reconversion of large industrial areas, substantially ensuring a strong institutional control over the evolution of the city and discouraging the creation of large mono-functional districts.

This mix of supporting politics and the abundance of cheap spaces helped attract young and creative people, creating a momentum of intensive cultural production and underlying the transition of the city into a post-industrial society and economy.

In 1990, a Rot-Grün coalition won the majority in the Municipality for the first time since the ‘30s. Among a national economic recession and a worsened social situation, the coalition was urged to tackle the widespread drug scene. Acting first with repression, and then with support, the clearances of the Platzspitz Park (1992) and Letten Areal (1994) changed drastically the central districts 4 and 5, normalising the public spaces and stimulating young artists and creatives to move in.

The Municipality was quick to channel this new positive energy, promoting several interventions to sustain it and fostering a boom of new small enterprises. The Bars and Restaurants Deregulation Act (1998) encouraged the opening of many restaurants and bars. The techno scene started reusing old abandoned industrial buildings and invaded the city with the first street parade, soon transforming Zurich into a renowned party location, while all over the city independent art galleries and other informal cultural spaces bloomed. Many former political activists became part of this new creative economy, which became a strong and profitable industry, actively sponsored by institutions and skilfully used as an instrument of city marketing.

Elmar Lederberger, Head of the Public Buildings Department (1998) and later Stadtspräsident (2002), used this new image of Zurich to promote a successful politics of urban regeneration. Thanks to the new agreements between real estate investors and the association of citizens signed during the Stadtforum (September 1996 – June 1997), a new zoning plan was approved in 1999, introducing significant simplifications for the approval of new development plans. Furthermore, the federal parliament modified the Lex Koller (May 1997), allowing Swiss building contractors to enter the stock exchange and de facto paving the way for foreign real estate investments.

These new policies and the injection of fresh international capitals triggered a construction boom that deeply transformed the city. In the following fifteen years, the old factories and vacant lots where the counterculture had thrived were gradually replaced by luxury apartments, shopping centres and offices, taking advantage of the vibrant environment created by the substrate of previous informal spaces.

Perla Mode (’06-’15), then and now

Perla Mode (’06-’15), then and now

Counterculture and City Government

We can see a specificity, a greatness in the experience of Zurich, which distinguishes it from other European practices. Its direct democracy, inclusive approach, and top-down support has proven to be extremely successful, transforming its internal contrasts into the tools to obtain the status of a sophisticated global city. On the one hand, the early alternative experiences have been progressively transformed into more durable and structured realities, able to move from a strategy of mere opposition to a more proactive one, as the successful examples of numerous building cooperatives show (Karthago, Dreieck, Kraftwerk 1, Mehr als Wohnen). On the other hand, after a first period of intransigent opposition, the Municipality understood the potentiality of these movements and started to support and finance them, creating an outlet for social tensions but also an important instrument for its own agenda. This interaction between movements and institutions created a symbiotic relationship that generated visibility, consensus, and wealth for both parties.

Nevertheless, this system seems today to be victim of its own success.

The chronic lack of affordable and available spaces is worsened by the impressive recent urban developments. The once overabundant former industrial areas have been progressively eroded and privatized. The competition for the use of the few spaces still available in the inner city incentives organization, financial support, and extended networks rather than spontaneity, freshness, and social critique. Many Freiräume were forced to turn into established spaces to survive, reducing the possibility to develop truly autonomous and alternative proposals.

The creative economy progressively assimilated the counterculture, generating an unsustainable model. Even the public patronage has been unable to stop this dynamic, on the contrary, it worsened the situation, rendering alternative projects more and more depending on public funding and therefore inevitably reducing their freedom and increasing their institutionalisation and normalisation. As put forward by the German sociologist Andreas Reckwitz in his book Die Erfindung der Kreativität, in the modern society capitalism transformed cultural production from opposition or critic of the system in a generator of mere entertainment, causing a loss in the relevance and quality of its contents and hindering experimentation and social renewal [2].

Zurich is today at the peak of its cultural richness and witnesses a boom of alternative building cooperatives, temporary uses and off-spaces. At a first glance, it seems like the promise written on the occupied houses of Tessinerplatzt and later in the main wall of Wohlgroth, “Alles wird Gut” (everything is going to be alright), has been fulfilled.

The present situation of the counterculture in the city, however, due to its unresolved contradictions and uncontrolled dynamics, risks to compromise this fragile balance and cause the disappearance of an exclusive heritage of culture and know-how. Without its rich counterculture, Zurich could lose its innovative uniqueness. There is today the necessity to reflect on how to reverse this trend and recognise the fundamental role of the Freiräume as incubators of sustainable visions for the city.

The movement of the last decades showed us that a different city is possible. Are we satisfied with what we have today? Or it is time to claim something more?

* Alles ist Gut is a collaborative research on Zurich’s counterculture and evolution of alternative spaces over the past fifty years. The project is composed by a book, an exhibition and a symposium. Through the voices of some of its protagonist and theorists, the book guides the reader in the (re)discovery of this scene, reflecting on the social production and appropriation of the urban realm.

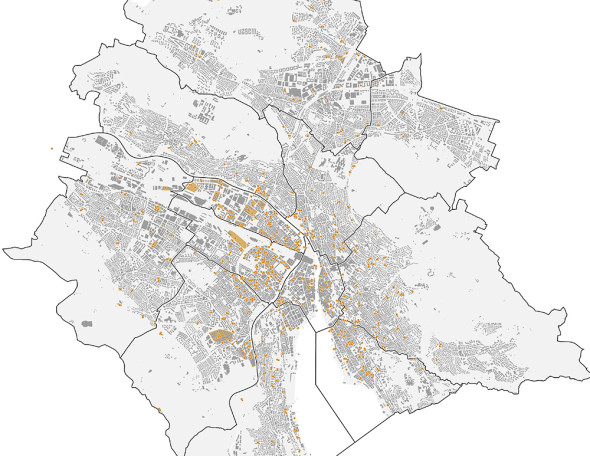

Alternative places in Zurich 1960-2015

Alternative places in Zurich 1960-2015

Notes

1. “Die enge gesellschaftliche Verquickung von Ästhetisierung und Ökonomisierung hat ohnhin bereits stattgefunden und es müsste für die staatliche Politik darum gehen, hier eine alternative Logik stark zu machen, die die Überhitzungen des Kreativitätsdispositivs versucht abzukühlen”.

2. “Junge und alte waren sich einig mit der Protestaktion fortzufahren. Nur wenn sich tausende von Mietern vereinigten und den Spekulanten trotzen, bestünde eine Chance, dass alle Leute eine Wohnung finden würden. Werte Anwesende, junge und alte Mitbürger, was heute Abend Erfreuliche ist, ist vor allem der Zusammenschluss von den jungen und von den alten”. (Vollversammlung im Volkshaus der Mieter Tessinerplatzt, Frühling 1971, SF DRS Archiv, in “Allein machen sie dich ein”, Mischa Brutschin, Zürich, 2010)

Bibliography

Manuel Castells, The City and the Grassroots: A Cross-cultural Theory of Urban Social Movements, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1983

Ursula Koch, Bauen in Zürich zwischen Utopie und Resignation, Stadt Zürich, Zürich, 1988, Pp. 8

René L. Frey, Stadt: Lebens- und Wirtschaftsraum, Verlag der Fachvereine vdf, Zürich, 1996.

Christian Schmid, The Dialectics of Urbanisation in Zurich: Global City Formation and Urban Social Movements. In: INURA, Possible Urban Worlds. Urban Strategies at the End of the 20th Century, Birkhäuser, Basel, 1998, Pp. 216–225

Heinz Nigg, Wir wollen alles, und zwar subito!, Limmat Verlag, Zürich, 2001

Thomas Stahel, Wo-Wo-Wonige! Stadt-und wohnpolitisches Bewegungen in Zürich nach 1968!, Universität Zürich, Zürich, 2006

David Harvey, The right to the city, in “New Left Review”, nr. 53, September–October 2008, pp. 23–40

Marc Angst, Philipp Klaus, Tabea Michaelis, Rosmarie Müller, Stephan Müller, Richard Wolff, zone*imaginaire, Verlag der Fachvereine vdf, Zürich, 2009

Mischa Brutschin, Allein machen sie dich ein, Zürich, 2010

Neil Brenner, Peter Marcuse, Margit Mayer, eds, Cities for People, Not for Profit: Critical Urban Theory and the Right to the City, Routledge, New York, 2012

David Harvey, Rebel Cities, Verso, London/New York, 2012

Henri Lefebvre, Spatial Politics, Everyday Life and the Right to the City, Routledge, New York, 2012

Philipp Klaus, INURA, Räume und Bewegungen der Kreativen in Zürich 1989-2014, Stadt Zürich, Zürich, 2015

Naomi Klein, Naomi Klein: Squatters In White Overalls, in “The Guardian”, n.p., 2017. Web. 30 Jan. 2017

Authors

Michele D’Ariano Simionato is an architect and curator. He studied Architecture in Ferrara and Spatial Design at the Zürich University of the Arts. His works have won several prizes and have been exposed also at Biennale Venezia, Theater Gessenerallee and Salon Suisse.

Marco Jacomella is an architect and urban designer. He holds an ETH MAS in Housing studies and a Master Degree in Architecture from University of Ferrara. After international working and teaching experiences, he currently practices as project architect in Zürich and conducts research on the possibility of housing as a common in Italy.

Related Posts

Questo sito usa Akismet per ridurre lo spam. Scopri come i tuoi dati vengono elaborati.

Lascia un commento